annelingua

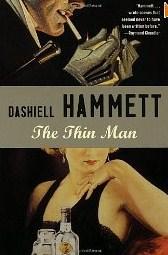

Any Human Heart

av William Boyd (forfatter).

Vintage 2004 Paperback

annelinguas eksemplar av Any Human Heart

Lesetilstand

Ønsker meg denne.Hylle

Ønskeliste_amazon(?)Lesedato

Ingen lesedato

Favoritt

Ingen favoritt

Terningkast

Ingen terningkast

Min omtale

Ingen omtale

Bokdetaljer

Forlag Vintage

Utgivelsesår 2004

Format Paperback

ISBN13 9781400031009

Språk Engelsk

Sider 512

Finn boka på biblioteket

Finner du ikke ditt favorittbibliotek på lista? Send oss e-post til admin@bokelskere.no med navn på biblioteket og fylket det ligger i. Kanskje vi kan legge det til!

Bokelskeres terningkastfordeling

1 1 3 0 0 0Diskusjoner om boka

Ingen diskusjoner ennå.

Start en diskusjon om verket Se alle diskusjoner om verketSitater fra dette verket

I think . . . I never really expected my life to be like this, somehow. What happened to those youthful dreams and ambitions? What happened to those vital, fascinating books I was going to write?

I believe my generation was cursed by the war, that “great adventure” (for those of us who survived unmaimed) right bang slap in the middle of our lives—our prime. It lasted so long and it split our lives in two—irrevocably “Before” or “After.” When I think of myself in 1939 and then think of the man I had become in 1946, shattered by my awful tragedy . . . How could I carry on as if nothing had happened? Perhaps, under these circumstances, I haven’t done so badly after all. I’ve kept the LMS show on the road—and there is still time for Octet.

And suddenly I wonder: is it more of my bad luck to have been born when I was, at the beginning of this century and not be able to be young at its end? I look enviously at these kids and think about the lives they are living—and will live—and posit a kind of future for them. And then, almost immediately, I think what a futile regret that is. You must live the life you have been given. In sixty years’ time, if these boys and girls are lucky enough, they will be old men and women looking at the new generation of bright boys and girls and wishing that time had not fled by—

That’s all your life amounts to in the end: the aggregate of all the good luck and the bad luck you experience. Everything is explained by that simple formula. Tot it up—look at the respective piles. There’s nothing you can do about it: nobody shares it out, allocates it to this one or that, it just happens. We must quietly suffer the laws of man’s condition, as Montaigne says.

Romanen åpner slik:

"Yo, Logan,” I wrote. “Yo, Logan Mountstuart, vivo en la Villa Flores, Avenida de Brasil, Montevideo, Uruguay, America del Sur, El Mundo, El Sistema Solar, El Universo.” These were the first words I wrote—or to be more precise, this is the earliest record of my writing and the beginning of my writing life—words that were inscribed on the flyleaf of an indigo pocket diary for the year 1912 (which I still possess and whose pages are otherwise void). I was six years old. It intrigues me now to reflect that my first written words were in a language not my own. My lost fluency in Spanish is probably my greatest regret about my otherwise perfectly happy childhood. The serviceable, error-dotted, grammatically unsophisticated Spanish that I speak today is the poorest of poor cousins to that instinctive colloquial jabber that spilled out of me for the first nine years of my life. Curious how these early linguistic abilities are so fragile, how unthinkingly and easily the brain lets them go. I was a bilingual child in the true sense, namely that the Spanish I spoke was indistinguishable from that of a Uruguayan.

Uruguay, my native land, is held as fleetingly in my head as the demotic Spanish I once unconsciously spoke. I retain an image of a wide brown river with trees clustered on the far bank as dense as broccoli florets. On this river, there is a narrow boat with a single person sitting in the stern. A small outboard motor scratches a dwindling, creamy wake on the turbid surface of the river as the boat moves downstream, the ripples of its progress causing the reeds at the water’s edge to sway and nod and then grow still again as the boat passes on. Am I the person in the boat or am I the observer on the bank?

Those were the years when I was truly happy. Knowing that is both a blessing and a curse. It’s good to acknowledge that you found true happiness in your life—in that sense your life has not been wasted. But to admit that you will never be happy like that again is hard.

I said I was fine, no really, life was OK, I was coping, writing a new novel, no, fine, fine, really fine. When we parted she held on to me tight and said, “I love you, Logan. Don’t let’s lose touch.” I couldn’t stop the tears and neither could she, so she lit a cigarette and I said it looked like rain wasn’t far off, and somehow we managed to part.

Legg inn et nytt sitat Se alle sitater fra verket