superior races - in elitist views

The epidemic is the culmination of the intellectual and spiritual

tradition of some of the richest and most powerful people alive,

many of them famous and respected figures from families

whose names are household words and held in high esteem by

the public.

Their indifference — or contempt — for the lives of common humanity

should not come as a surprise, nor be hard to believe.

Since at least the height of British colonial domination of

the world,

there has been a potent strain of thinking among "aristocrats"

about superior races

(white, English speaking, educated and rich)

and inferior races

(white or black or colored, uneducated and poor).

The entire British colonial system was based on the ruthless

domination by a few of the "superior" over vast numbers of

the "inferior."

America itself was founded in rebellion against that domination.

The American Revolution was an overthrow of those old ideas

about who should rule — and how.

And then the new Americans turned right around and did the same

thing to their own "inferiors,"

allowing slavery for blacks and committing genocide against

Native Americans with a rapacity that would have gratified the

most ruthless British colonialists.

Philosophers revered as great thinkers by the British aristocrats

of those centuries

openly expressed their views that

the inferior peoples of the planet must not be allowed

to increase sufficiently in numbers

to use up the earth's precious natural resources

and, eventually, to overrun by sheer numbers the existing

political and economic system.

The most prominent 18th Century spokesman for the British

East India Company policies of global genocide

was the economist Adam Smith.

His book, The Wealth of Nations, is still required reading

in college economics classes.

He wrote several works on forced population reduction,

the most notable being The Treatise of Human Nature and The

Theory of Moral Sentiments,

in which he placed mankind on the level of animals.

Smith's ideas were advanced in the 19th Century by philosophers

as prominent as Thomas Malthus,

another high-ranking employee of the British East India Company.

To the acclaim of the British upper classes, Malthus actually

wrote in the mid-1800's:

"All children who are born, beyond what would be needed to keep up

the population to a desired level,

must necessarily perish,

unless room be made for them by the death of grown persons …

We should facilitate, instead of desperately trying to impede,

the operation of nature in producing this mortality,

and if we dread the all too often visitation of the horrid form

of famine, we should sedulously encourage the other forms of

destruction which we compel nature to use."

Malthus' modest proposals included that the poor be educated

into habits of filth rather than cleanliness

and that poor villages should be built "near stagnant pools

and particularly encourage settlements in marshy and unwholesome

situations [sites]."

And he encouraged that restraint be enforced upon those

misguidedly benevolent men who would try to protect the poor

from contagious diseases.

Malthus was a respected writer of his era,

and though not one American in a thousand has read his work

since some boring college class, his name remains famous.

His writings were eminent enough to be responsible for

the invention of a word that remains in our language even now:

Malthusian.

Meaning: "Of / pertaining to the theory of Thomas Malthus that

population tends to increase faster than food supply,

with inevitably disastrous results unless the increase in

population can be checked."

Inevitably disastrous results unless the increase in population

can be checked. Precisely.

And in one sentence, the meaning of "Malthusian"

captures perfectly what the AIDS epidemic is really all about:

Population control.

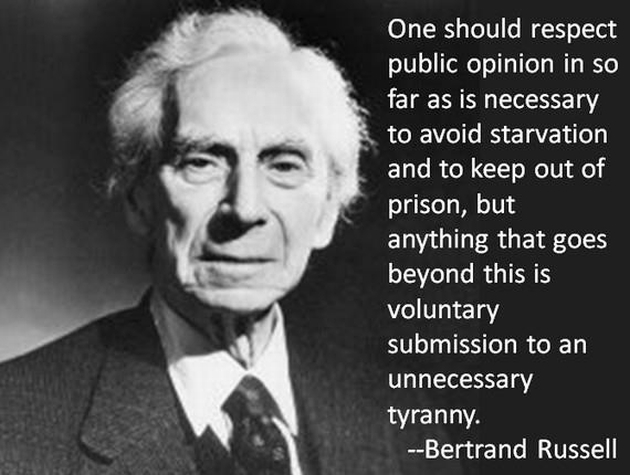

Malthusian philosophy was heralded in the 20th Century by

esteemed British writers who included H. G. Wells

(of "War of the Worlds" fame) and Lord Bertrand Russell.

Near the end of his long life, Lord Russell won acclaim among

antiwar activists for his outspoken opposition to American

involvement in Vietnam. But what they didn't know was that

he just thought war was a horribly messy and inefficient way

to kill people.

Not to mention the property destruction and expensive munitions.

Throughout his career, Lord Russell spoke of the aristocratic

aspiration toward a more refined form of genocide.

In 'The Impact of Science on Society', he made it clear

what they had in mind:

"I do not pretend that birth control is the only way in which

population can be kept from increasing. There are others,

which, one must suppose, opponents of birth control would prefer.

War, as I remarked, has hitherto been disappointing

in this respect,

but perhaps bacteriological war may prove effective.

If a Black Death could be spread throughout the world

once in every generation,

survivors could procreate freely without making the world

too full.

There would be nothing in this to offend the conscience of

the devout or to restrain the ambition of nationalists.

This state of affairs might be somewhat unpleasant, but

what of it. Really high-minded people are indifferent to

suffering, especially that of others."

But of course. How else to run an empire?

In 1953, when Lord Russell's book was published, there was

very little public knowledge of bacteriological warfare.

Yet he spoke of it knowingly and lovingly, and he clearly

indicated that poor nations would be targeted.

That virulent strain of thought continues — and reaches

to the top.

In 1962, the CIBA foundation held a symposium,

"Man and His Future," at which the keynote speaker was

Francis Krick.

His favored tactics of population control included putting

a chemical that would cause sterility in the water supplies

of those nations he judged as "not fit to have children."

Other nations deemed fit would be given a license to

purchase an antidote.

"This approach may run against Christian ethics," he said

in a nice touch of understatement,

"but I do not see why people should have a right to have children.

We might be able to achieve remarkable results after twenty

or thirty years by limiting reproduction to genetically superior

couples."

He talked about the benefits that could come to a country that

"improved its population on a grand scale."

What type of people was Frick talking about?

A study of his work leaves no doubt that "limiting reproduction

to genetically superior couples," as he wished to do,

would exclude Negroes, Jews, Gypsies and the Asian races.

The year was not 1939 but 1962, and the country was not

Nazi Germany, but the United States of America.

These were not the musings of a deranged madman, but the

philosophical essence of one of the foremost microbiologists

in the world. Francis Krick was a winner of the Nobel Prize.

And thirty-some years later, here we are.

Those responsible for the AIDS epidemic have at long last

created the perfect tool for their Malthusian solution

to their most pressing problem:

Population control.

( kap.fulltekst )